Adolescence in schools: Should fictional drama dictate government policy?

| Updated:

Netflix’s Adolescence has sparked national conversation and political debate, but questions remain about what concrete actions should follow as the Prime Minister announces plans to screen the Netflix hit in schools nationwide.

Listen to this article

Read time: 4 minutes

In brief:

- Netflix's Adolescence has become a TV phenomenon with 25 million viewers worldwide, sparking conversations that reached Downing Street where PM Keir Starmer announced the show will be made available in all UK secondary schools.

- Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch has criticised the political response to the show, arguing that creating policy based on fiction rather than reality is problematic.

- The News Agents question the lack of specific policy proposals from Starmer in response to the show.

What’s the story?

It’s fair to define Netflix’s Adolescence as not only a TV hit, but a TV phenomenon, watched by 6.45 million people in the UK in its first week alone, and by almost 25 million people worldwide since its release.

The show hasn’t only had an impact on the streaming service’s viewing figures, it’s started a conversation that’s spread from the living room, to social media and all the way to Downing Street.

When he visited The News Agents last week, the show’s co-creator Jack Thorne said he’d like to talk to the Prime Minister about the themes in the show that have hit a nerve nationwide.

His wish became a reality on 31 March, when Keir Starmer, who said he had watched the show with his teenage children, held a round-table at Number 10 with writers and producers of the show, including Thorne.

Starmer confirmed the show will be made available to watch in all secondary schools across the UK, with healthy relationships charity Tender providing guidance and resources from teachers, parents and carers.

Despite the number of viewers and discussion in the highest political circles, there’s one person who hasn’t watched it - Kemi Badenoch.

The Conservative leader has said she hasn’t had any time to watch the four-part series, telling LBC’s Nick Ferrari; “I'm not going to watch every single thing everybody is watching.”

Lewis Goodall notes that it is “classically contrarian” for Badenoch to not have watched it; “She probably hasn't watched it because everybody else has seen it and liked it”.

Badenoch criticised the political hype that’s come in the aftermath of the show, saying that while it “touches on a problem in society,” there are bigger problems “such as islamic terrorism”.

“Creating policy on a work of fiction rather than reality is the real issue,” she added.

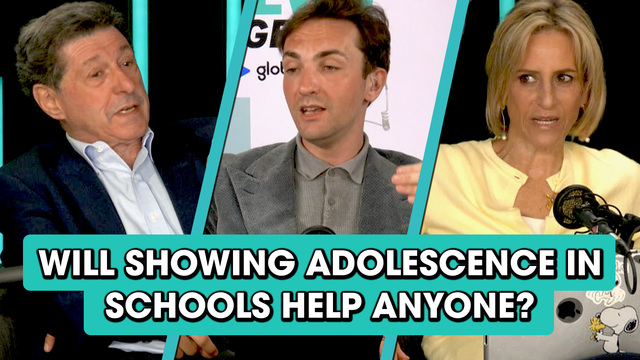

Will showing Adolescence in schools help anyone?

What’s The News Agents’ take?

Unlike ITV’s hit drama, Mr Bates vs The Post Office, which centered on a real-life scandal and worked to seek a solution, for those who were victims of the Horizon scandal to receive compensation, Adolescence does not, Emily, Jon and Lewis agree, have a clear call to action once the screen goes dark.

“You start to think; why are you showing it in schools? What is the lesson? And if there is something for the government to do, well maybe the government should do it,” Jon says.

While Lewis liked the drama, he admits he never really got the sense of what they were trying to say beyond there being an “abstract problem” in young boys.

“I think the Prime Minister has taken that up without being very specific.”

In which case, maybe Kemi Badenoch is right that politicians shouldn’t make policy off the back of a fictional TV drama - and if she’s wrong, and they should, what policies are they?

Emily says she doesn’t have the answer - and while she likes the idea of Adolescence being shown in schools, she doesn’t think Starmer does either.

“The Prime Minister was asked directly about this; is it about mobile phones? Is it about toxic masculinity? Is it about a really shit education system which lets kids fall through the cracks?

“He didn't know. He couldn't answer that.”

The reaction from Downing Street then, is a classic case of when “symbolism starts to matter more than actual politics and policy,” Lewis says.

“Prime Minister, if you think there's a real problem with social media companies, for example, why don't you regulate them?

“If you think there's a problem in terms of children having access to smartphones and watching too much Andrew Tate, we could do what the Australians have done, which is ban smartphones for under 16s.”

“Explain precisely what you think the problem is, or shut up.”

But, if no one can identify what policy changes should be introduced as a result of the problems the show highlights, maybe “Starmer is getting it right, then,” Jon suggests.

“You welcome the conversation. You welcome the raising of consciousness, but the government doesn't automatically jump towards legislation.”