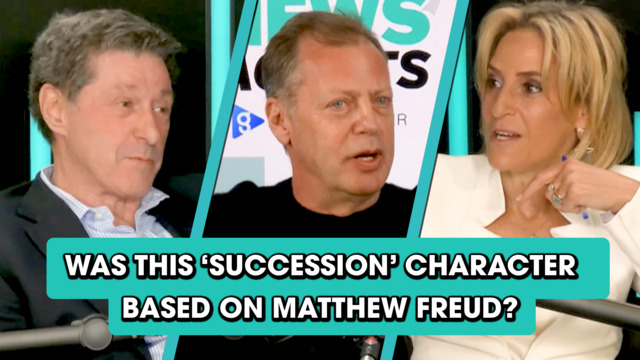

Matthew Freud: 'Tom in Succession wasn't based on me, but another character might be'

| Updated:

Matthew Freud, described as one of the most influential people in the UK, has spent four decades working in “crisis PR” for some of the biggest names in showbiz and politics. How has the landscape changed, and was he really the influence for a character in HBO’s Succession TV series?

Listen to this article

Read time: 7 mins

In brief…

- Matthew Freud tells The News Agents about a cultural shift since the 1980s from the media admiring celebrities to seeing them as “cannon fodder”, blaming this on a decline in public trust in people in authority.

- Freud denies the character of Tom Wamgsgan in Succession was based on him, but does believe there was someone else on the show who he may have influenced.

- Despite constant criticism of the Labour government, he says it is too early to judge its political achievements, but admits it has spent too much time reacting to “trivial” issues during its time in power.

What’s the story?

It’s not often Matthew Freud speaks to the press – after all, it’s his job to pull the strings from behind the scenes.

The PR guru describes himself as having spent “40 years in hiding”, with his role to promote and amplify the big name he’s worked with across entertainment, business and politics – often stepping into what is known in the industry as “crisis PR”.

“I would say the worst thing that you can ever hear is someone say: “Oh, you should call Matthew Freud” – because it means things have gone wrong,” he tells The News Agents.

He says that his role in these situations is to coach the person involved through the situation, highlight that their status means there is a “legitimate” media interest in their personal or professional life, and “encourage them to deal with the actual problem.”

The 61-year-old is well-connected, and has, as Emily Maitlis says, “one of the most famous surnames in the world. He’s the great-grandson of Sigmund Freud and ex-husband of Elisbeth Murdoch, but insists that growing up with a famous surname is “a form of identity abuse”.

He pursued a different vocation to his famous great-grandfather, founding Freud Communications in 1985, at a time when Public Relations was a new industry, and has previously been described as one of the most influential people in the UK.

In the forty years since, Freud says he has witnessed the media go from admiring celebrities and figureheads to considering them “cannon fodder”, with publications developing a “voracious appetite” for digging into the goings on behind the scenes in the lives of big-name stars and personalities.

Freud’s take on the Murdoch empire

Last year a high profile court case concerning Freud’s ex-wife and daughter of Rupert Murdoch, Elisabeth Murdoch, made headlines.

The Nevada case concerned the succession of Rupert Murdoch's media empire (most notably Fox and NewsCorp), and his intention to give control to his son Lachlan Murdoch, instead of sharing it equally with siblings Prudence, James and Elisabeth.

It was a real-life battle fans of HBO's Succession will be all too familiar with.

Freud says the complications in the Murdoch case, like the TV show, came from the balance between the business and the complicated family dynamics at play in the case.

"Families are hard enough, but when there's a shared identity that makes it much more difficult, because everyone is reflecting on everyone else, and that's a difficult dynamic," he says.

"When there's a lot of money involved, that can definitely become the defining dynamic around a family."

He adds that families like Murdoch's have an ecosystem within them which can "infantilise" the people inside the structure.

But he adds that often, in situations like that of the Murdochs, taking family issues into the legal arena may not always be the best route to a solution.

"The temptation is to proxy a battle that is an emotional and personal one into a legal one because it's got a framework, or into a media one because it's got a narrative that you know can be played or manipulated," Freud says.

"You would imagine that any people who fundamentally love each other, if they're able to talk to each other openly and freely in a safe space, they'll probably resolve whatever difficulties they have."

Did Matthew Freud inspire a character in Succession?

Things played out in the Murdoch trial a little differently to how they did in Succession.

On TV, the reins of power fell to Tom Wambsgan (Matthew MacFayden), the husband of Siobhan (Shiv) Roy, who was based on Freud’s ex-wife Elisabeth Murdoch.

As Shiv’s character was based on Elisabeth Murdoch, it’s been suggested that her TV-husband, Tom Wambsgan, was then inspired by Matthew Freud.

“In the first series my sense was that Tom wasn't me,” he says.

“But there was a secondary character in the first series who was a liberal lobbyist (political strategist Nate Sofrelli, played by Ashley Zukerman) who Shiv was having an affair with and drew her over to a more progressive way of thinking – so I thought that was probably me.”

“My assumption was that that character was possibly going to develop, and might have been very loosely based on me.”

Whatever the truth behind the influence on these characters, Freud describes Succession as “one of [his] favourite TV shows of all time”

Emily points out the show was incredibly well informed, but Freud says he’s never met the show’s creator and writer Jesse Armstrong and “has absolutely no idea who sourced it” - he also confirmed, unlike Tom, he never bought his father-in-law a very expensive watch.

Was this 'Succession' character based on Matthew Freud?

Why did the public relationship with celebrity change?

The change in the media, he believes, is ultimately due to the changing perspective of the public and how we treat and respond to celebrities and people in positions of power – and a steady decline in the level of trust we place in those in authority.

“The way that people absorb and process the information they're getting from both social media and conventional media, is, is not trusting,” he says.

“There was a period 30/40 years ago where we deferred to authority, and that became an age of reference, where we take what a doctor said, or what the media said and listened – but you then look at other points of view, and you make up your own mind.”

He says today’s world is an “age of indifference”, making the truth hard to discern for many, and trust hard to win.

“I think people have really tuned out of this idea that there was a singular point of view, or that there was a singular opinion, and that that was the truth,” he adds.

And like so many issues facing the world in 2025, there are two key instances that highlight this decline in public trust.

“Both Brexit and the election of Trump were, to my mind, an act of terrible collective self harm on behalf of the UK with Brexit, on behalf of America with a two term Trump agenda,” he says.

“One of the conclusions you've got to draw is that people don't care.”

Does the UK’s Labour government need crisis PR?

But if there is one person, and organisation, that you might think needs Freud PR expertise right now, it's Keir Starmer and the current Labour government.

In less than a year in power it has been dogged by controversies over Taylor Swift tickets, who’s paid for Starmer’s wardrobe, Angela Rayner's council house and more distractions from its attempts to resolve the issues left by 14 years of Tory rule.

"In 10 months in government, you can't actually do anything," Freud says.

"Tony Blair, in his book on leadership, says you can't do much in a single term – you need two terms to change."

He says 10 months is far too early to judge Labour's time in power.

"The narrative is that they're in crisis, that they're not decisive enough. They take freebies, who paid for those glasses? Or, you know, did Angela Rayner pay enough tax on a house that she sold 15 years ago?

"The public are reliant on a narrative that is being fed through a very defined political agenda."

He says the government has a number of "tangible achievements" in its first ten months in power, but due to the UK's slow and "laggy" legislative process, describes covering politics in real time as a "pretty pointless pursuit".

"The dangerous aspect of a media-driven narrative is that it's distracting. So trying to manage it is a waste of important time," he adds.

"I think this government has spent too much time reacting to the day-to-day incoming inquiries about incredibly trivial issues."